A recent documentary, Persona: The Dark Truth Behind Personality Tests, might be concerning for people who use personality assessments. There are certainly concerns when it comes to using any type of assessment that should not be overlooked. However, the information presented in this documentary has elicited strong enough reactions that assessment professionals have felt the need to respond. The Society for Industrial and Organizational Psychology has released a statement summarizing some ways the documentary didn’t reference the body of research that supports personality assessments. Tilt has already published two blogs describing personality assessments for the workplace and why we built a better personality assessment that I recommend reviewing if you are interested in better understanding personality assessments. But, after watching the documentary myself, I thought that it might be helpful to expand on the statement provided by other professionals and describe several research-based findings not presented in the documentary.

Most research doesn’t really support “types.”

The documentary focused fairly heavily on defining personality in terms of “types,” which is a common way many people think about personality. There are what seems like an infinite number of quizzes on the internet that can tell you which letters, color, animal, or movie character you are. This, along with the prevalence of the Myers-Briggs Type Indicator (MBTI), has led many people to believe that personality assessments are used to categorize people. However, most personality researchers would agree that personality traits are actually on more of a spectrum than divided into types. This means that instead of asking someone whether they are an introvert or extravert, the better question is asking how introverted they are. Further, the personality types that many assessments describe are not good predictors of important outcomes like job performance. Thus, thinking about personality as based on types rather than how high or low you are on a spectrum is inconsistent with most research into personality.

So why has the idea of types become so dominant? People like the idea of types because they are simple and help them feel connected to similar people, even if it’s not supported by research. In fact, the Persona documentary showed that people appreciate feeling understood and knowing that there were others “like them.” When you have concrete distinctions, the world is easier to understand. However, it is fairly easy to see why types don’t hold up well when considering how personality traits actually work. Many human attributes, including personality traits, are distributed on a normal distribution, pictured above. This means that most people have an “average” level of personality traits, which is represented by the large proportion of people in the middle of the graph. If you take a distribution like this where most people are average and divide it in half to create “introverts” and “extraverts,” then people who actually have very similar scores are placed in opposite categories. For example, in the picture above, 95 could be labeled an “introvert” and 101 could be labeled an "extravert," which implies people with those scores are fundamentally different. However, those scores are actually much closer than the scores of two introverts or two extraverts could be. An individual with a score of 10 and another with a score of 95 have vastly different scores, but are both labeled introverts. This shows how much information is lost by forcing people into unchanging types.

Types and True Tilts

If you are familiar with Tilt, you may be wondering how this perspective is consistent with the results of the True Tilt Personality Profile™ assessment, which presents results describing one of four True Tilts. A True Tilt is not the same as a permanent personality type. A True Tilt is a set of preferences for using certain character strengths. A more general example of a preference might be preferring pizza to tacos. We know that is true most of the time, but it likely isn’t always true. Similarly, someone with a Structure True Tilt generally prefers brutal honesty to a less than true compliment, but there may be some days when someone with a Structure True Tilt isn’t ready for brutal honesty. General tendencies like these are easy to explain and apply, so knowing them can be useful in our everyday lives even though we all actually exist on a spectrum.

The goal of a personality assessment isn’t to trick you.

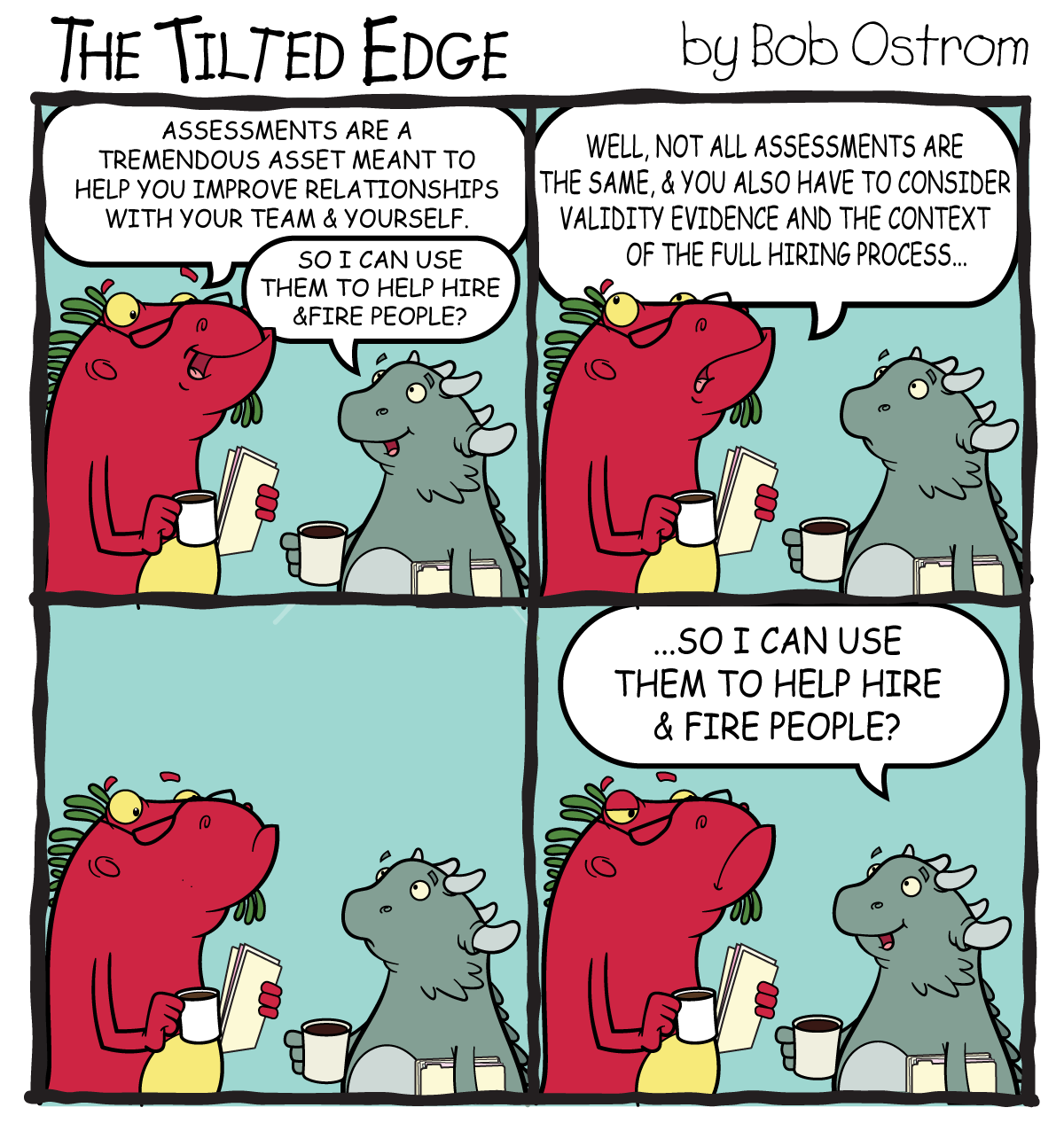

A prevalent theme in both the Persona documentary and any online search of personality assessments is how to beat a personality test. First, although many people may refer to personality assessments as “quizzes” or “tests,” they are more accurately referred to as “assessments.” A test has correct and incorrect answers, but personality assessments have no inherent right or wrong. The purpose is to describe stable preferences and tendencies for thinking, feeling, and behaving. Some preferences may be more advantageous than others in certain situations, but there is no “best” or “correct” personality. Some personality traits (traits on a spectrum, not types) are related to higher performance in certain jobs, so having a high or low level of that trait can affect job performance, job satisfaction, and organizational fit. If you have two candidates who are equally qualified for a position, but one has a set of personality traits that may fit better with the requirements of the job, then that information could be used to choose between them. However, information besides personality should be used when making hiring decisions. People are complex, capable of learning, and make decisions based on more than their personality. This means that even if their personality suggests one type of behavior, they could behave differently because they have learned what is better in that situation or the situation has very strong cues regarding appropriate behavior.

When you view a personality assessment as a “test,” it can lead to the impression that the questions are trying to trick you into choosing the wrong response. So, many people seem to worry that personality assessments used in the workplace are trying to trick them. However, this is largely counter to best practices in assessment construction. A respondent may not interpret an item the same way the assessment creator intended, so it is the responsibility of the assessment creator to try to communicate the meaning of each item effectively. Assessment creators follow established guidelines to make sure that items are as clear as possible. For example, items that contain two separate ideas (referred to as being double-barreled) should be avoided. An item like “I am exciting and optimistic” actually asks two questions, which is confusing because a respondent could be only optimistic or only excited, and then it is unclear how to respond. Assessments created following best practices avoid these types of items. Further, assessments created using the most common assessment development process utilize multiple items to tune in to the same trait. This means that the response on any one item should not determine someone’s score, so if it is misunderstood, there are other items that can assess the trait. For example, two items like “I enjoy having a lot of people to talk with” and “I prefer hobbies with social interaction” are both intended to measure extraversion, and the responses to both are used to compute the extraversion score. Following best practices like avoiding confusing items and using multiple similar items to find more accurate scores should minimize “trick questions,” and any items found problematic should be updated or replaced.

Different personality assessments are not interchangeable.

The Persona documentary provided a history of the MBTI and more briefly referenced a few assessments used in hiring, but all personality assessments are not created equally. Any review of personality assessments as a category cannot say much about any one of the many assessments that exist. They are based on different models of personality, written by different people, and validated and used in different ways. For example, different assessments intended to measure the same model (e.g., the Big 5) can vary widely in length, type of assessment (self-report, forced-choice, interview-based), and rigor in the development and validation processes. Further, if you carefully consider the definition of “validity” in assessment development, you’ll find that there is no such thing as a globally valid assessment. Validity refers to the degree of evidence supporting an assessment’s appropriateness for drawing inferences about certain criteria. So, evidence for the validity of an assessment is context-specific.

For a simple example with a different kind of measurement tool, a ruler is a good measure of length (with some degree of error in between the markings) but has little validity as a measurement of mass. Similarly, personality assessments are only valid for the specific purposes for which they have been designed and evaluated. One assessment may be a very effective developmental tool but completely inappropriate for hiring. Another may be relevant for job performance in one position but have almost no validity for a different job. If you plan to use a personality assessment, you should know whether it is valid for what you want to use it for. It is critical to evaluate personality assessments individually instead of as a category.

Personality assessments have a relatively low adverse impact.

Another prevalent theme in the documentary was how using personality assessments in hiring can impact different groups of people. Evaluating whether an assessment works similarly for different groups of people is crucial to building a diverse workforce and following legal guidelines designed to protect people from bias. From a legal perspective, adverse impact is defined as a ratio of the proportion of minority group applicants who were hired to the proportion of the majority group applicants who were hired. A problematic value is less than .80. For example, if 50 people in a minority group apply for a job, and 3 are hired, the proportion hired is 3/50 = .06. If for that same job, 300 people in the majority group applied, and 21 were hired, the proportion for the majority group is 21/300 = .07. The adverse impact ratio is .06/.07, which is about 0.86. Based on the criteria in the Uniform Guidelines, this value is larger than 0.80, so the rate that minority group applicants are hired is similar enough to majority group applicants that it is not considered an adverse impact.

Although the results for specific assessments vary, personality assessments typically demonstrate small differences between groups. This means that, in general, they don’t tend to disadvantage different groups. In fact, many professionals recommend using personality assessments in conjunction with cognitive tests in an attempt to reduce the overall bias in the employee selection process.

No one should be hired based solely on personality assessments.

One question that I had throughout the Persona documentary was what are the other parts of these hiring processes? A personality assessment should certainly never be the only thing used to make hiring decisions. Common sense says that employers should consider things like whether the applicant is qualified for the position before assessing their personality. No matter their results on a personality assessment, someone who has no relevant experience might not be a good hire, and that should be reflected in the hiring process.

The best practice way to follow this common-sense notion is to ensure that all hiring systems are based on the results of recent and thorough work analyses. A work analysis is an investigation of the activities a worker performs, the worker’s personal characteristics, and the context for the work. This analysis is the basis for determining the knowledge, skills, abilities, and other characteristics (KSAOs) needed to perform a job. An effective selection process should measure the full range of relevant KSAOs determined by the work analysis. Thus, there are likely no single tests, interviews, or assessments that are able to determine whether an applicant has all of the KSAOs. A combination of techniques like interviews, resume reviews, tests, work samples, and personality assessments can provide more of the information you need to hire the best candidate.

The Bright Side

Personality assessments are not without flaws and potential for misuse, but they are not as dark as they might seem. If you understand how to evaluate the validity evidence for each specific assessment and know what kind of assessment is most appropriate for your purpose (e.g., development or selection), then you can escape many of the potential misuses of personality assessments. They aren’t “tests” that are trying to trick you so that you don’t get a job. Some personality assessments (with appropriate reliability and validity evidence) can be utilized as a part of a comprehensive hiring process, and they may even reduce adverse impact. Other assessments can be effective tools for individual, leader, and team development. Understanding your patterns of thoughts, feelings, and behaviors and the patterns of those around you can help inform more effective interactions.